Through Time and Memory: The Atassi Family’s Cultural Archiving Journey

Regional archives preserve local history and protect cultural identity. Shireen Atassi reflects on the Atassi Foundation’s origins and its lasting dedication to Arab art and heritage. She highlights how the Foundation – especially through MASA (Modern Art of Syria Archive) – safeguards creative legacies and enriches global understanding of the region’s artistic history.

Interview with Shireen Atassi

Sometimes, it is not the passage of time that poses the greatest threat to the preservation of important historical accounts and materials – it is human conflict. Since the outbreak of Syria’s civil war in 2011, the country has endured unimaginable loss and destruction.

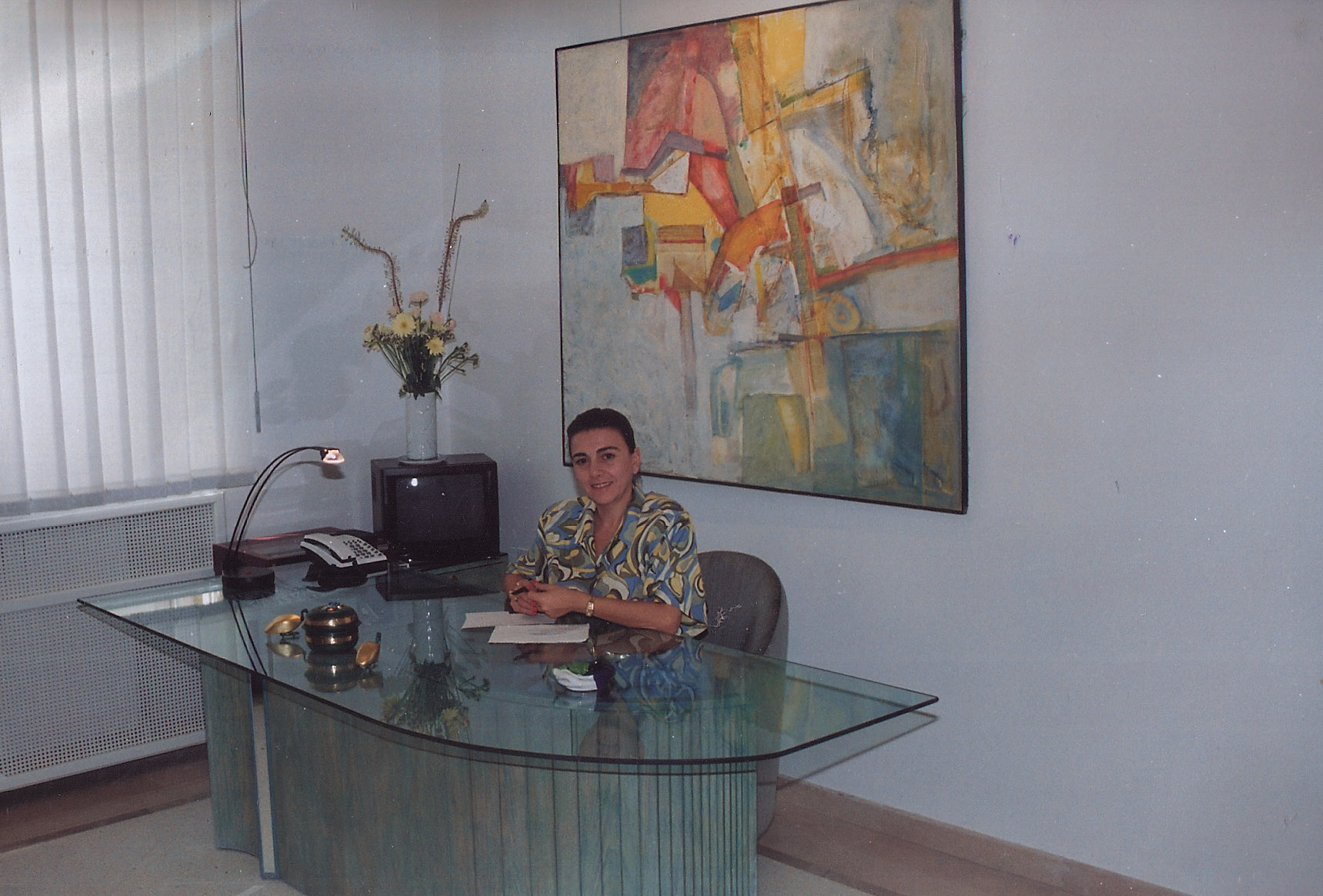

Early on, Shireen Atassi and her family felt compelled to preserve the history of Syrian art. In 2016, building on the legacy of the Atassi Gallery, which was founded by Shireen’s mother and aunt, Mouna and Mayla Atassi, in 1986 and was central to Syria’s independent art community, they established the Atassi Foundation, a non-profit arts initiative. It is dedicated to protecting and promoting Syrian art and bridging the country’s creative past with the voice of its future. Today, Shireen Atassi leads the Foundation as Director. A passionate art and culture entrepreneur, she also speaks internationally on Middle Eastern art, heritage, and philanthropy.

Q: What led you and your family to establish the Atassi Foundation, and what was the initial motivation?

The family began circulating the idea of establishing a foundation in 2014, as the civil conflict in Syria escalated into a devastating war marked by destruction, death, and mass displacement. In the midst of such tragedy, we felt a strong need to show a different side of Syria to the world – the creativity, the culture, and the enduring resilience of its people.

Since we had already established an art collection in 1986, which we had continued to grow and curate over the years, the idea emerged to share it with a wider audience by making it accessible online. From there, the concept slowly evolved. Given my mother’s decades-long experience running one of the most prominent Syrian art galleries, the family felt that, with its network and her expertise, setting up a foundation would be a more effective way of reaching our goal of celebrating, promoting, and preserving Syria’s rich cultural heritage. Two years later, in 2016, we officially launched the Foundation in Dubai.

Source: Atassi Foundation

Q: One of your latest initiatives is the Modern Art Syria Archive (MASA), which aims to document and preserve Syrian art archives and historical materials by Syrian artists. How did the idea emerge?

We recognized that Syrian art was largely underrepresented, both regionally and internationally, and the lack of primary research materials, and the difficulty accessing existing ones, were significant contributing factors. Due to the war, there was heightened fear of losing archives, documentation, and historical materials. I was also struggling to conduct research in this environment but felt that there had to be a meaningful way to contribute.

That’s when I began learning about how archives are designed, structured, and preserved. During the 2020 global lockdown, I had the opportunity to study my mother’s gallery archive in Damascus, which contained thousands of artwork slides, exhibition materials, purchase records, photographs, and newspaper clippings. It felt like a banquet of Syrian art history – and became the foundation for MASA.

Today, we have five archive collections that are published on a specially built platform that functions as a searchable repository. There are interlinks, research themes, and topics that make the experience come to life for the user. Another collection is scheduled to come up later this year, and then three for next year.

Q: Where do you see the importance of local and regional Arab archives being established? What narratives do you think are at risk of being lost if local archives didn’t exist?

Archives are so much more than simply a repository for records. I may be building an art history archive, but what it represents extends well beyond that classification. Not only does it show the activity of my mother’s gallery, it also reflects the social and cultural life in Syria during the 1990s and early 2000s. The archive is a snapshot of what people were interested in, concerned about, and responding to.

In the Arab world, we have lived with the risk of our histories being erased, fragmented, or mispresented.

If we don’t take responsibility for documenting and reclaiming our narratives, we’re leaving it up to others and their interpretation of us. And I think that is a real danger that could negatively impact future generations.

We need to be able to understand ourselves, not only for accurate historical perspectives but also to enable us to envision and shape our future. This is especially important now, as we have an entire generation that is dispersed and disconnected from their homeland, without any physical contact with the region. We need to help them understand and reconnect to where they came from and provide a sense of belonging. I believe archives are a powerful tool for doing just that while also teaching us about who we are and where we come from.

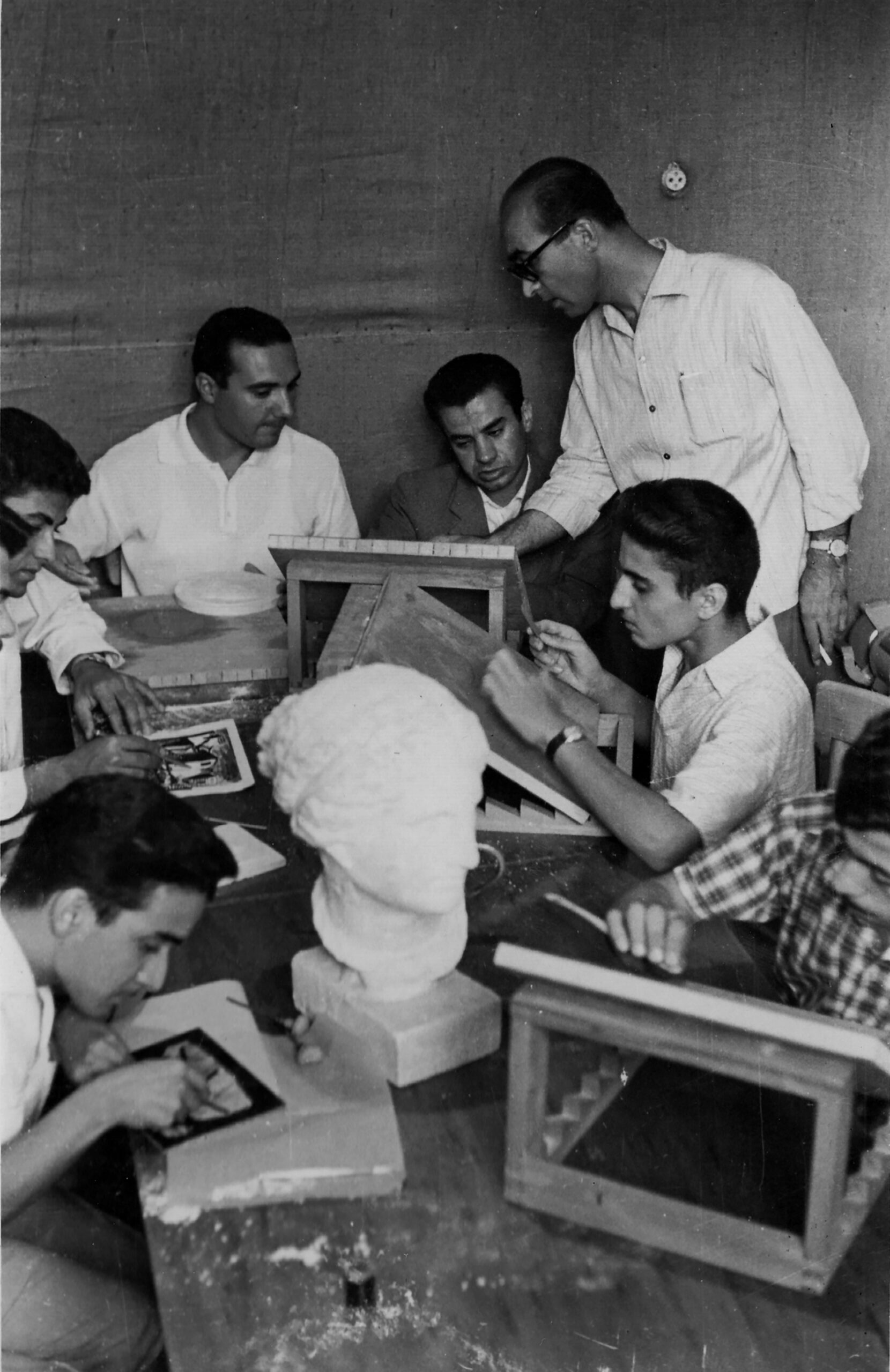

Source: Mahmoud Hammad Archive in MASA, the Modern Art of Syria Archive

initiative by the Atassi Foundation.

Q: Is there a parallel between how families preserve their own histories and how communities preserve cultural narratives? How do cultural memory and family legacies relate?

Absolutely, because both explore memory, identity, and continuity. In families, it often starts with storytelling and whether experiences are shared and passed down; whether photographs, letters, and heirlooms are kept. Communities also build their cultural narratives through stories, documents, newspaper articles, and photographs. In both cases, we need to give meaning and context to the material through oral accounts or deeper historical research.

I believe there will always be an interconnection between families and communities through social, political, and historical contexts, but I also think the motivation for preserving family or community history doesn’t need to be extravagant. Sometimes, it’s simply wanting to understand a grandparent more deeply, or to reconnect with a place or time through fragments of memories.

What’s beautiful is that this personal curiosity often leads to discoveries that resonate with others. A single photograph can mean different things to different people in the same family or the same community, further underscoring the importance of preserving and sharing our past.

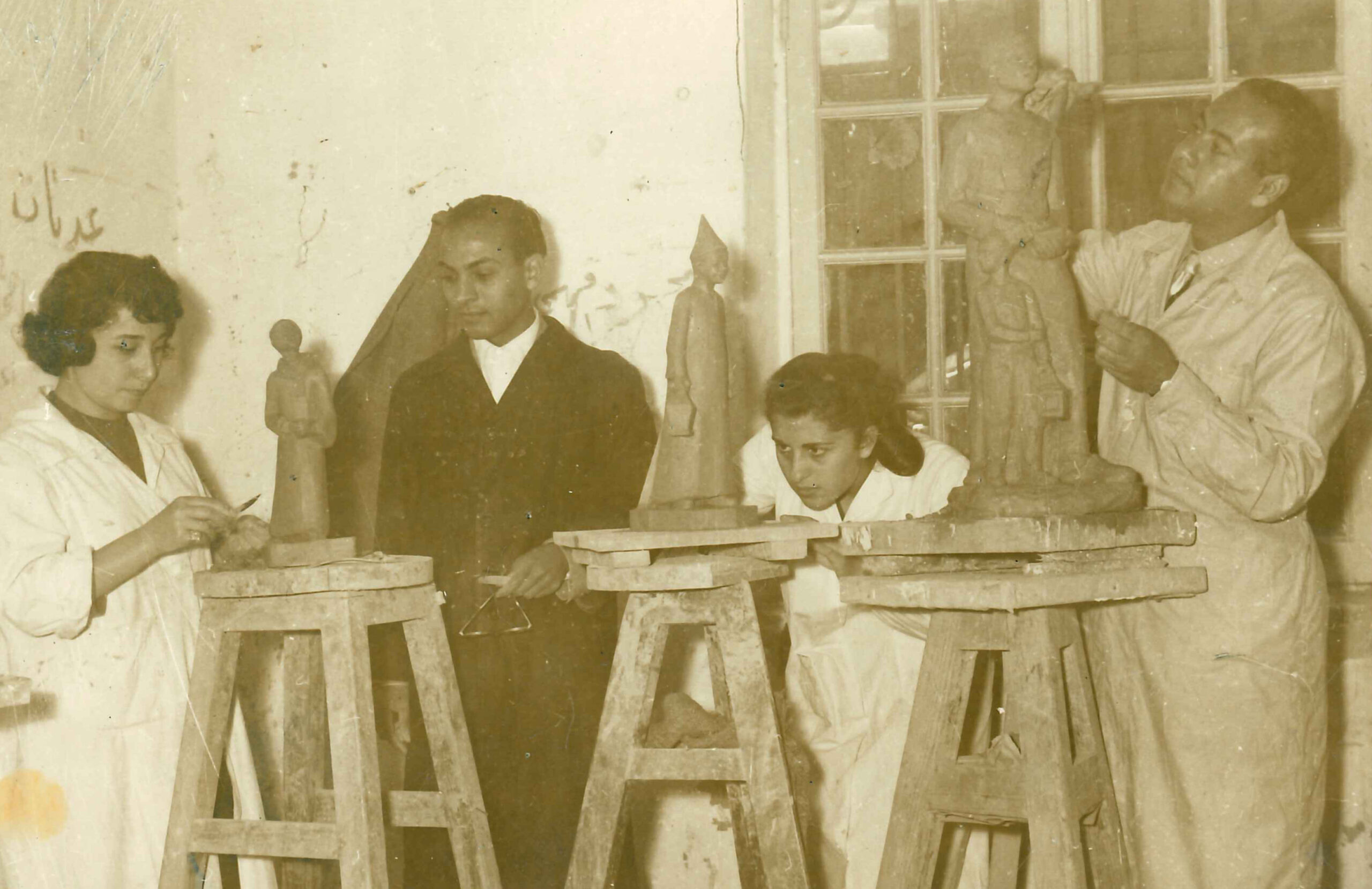

Source: Leila Nseir’s Archive in MASA, the Modern Art of Syria Archive

initiative by the Atassi Foundation.

Q: How do you envision the future of MASA? What do local or regional archives need to thrive and remain relevant in a rapidly shifting cultural and technological landscape?

MASA was created to serve as a key resource for anyone studying or engaging with modern or contemporary Syrian art. While continuing to expand the content is important, it’s equally essential that we ensure it is activated. If an archive isn’t being used, it risks becoming obsolete, no matter how valuable its contents.

From the beginning, we’ve been highly focused on archive accessibility. We wanted it to be available to everyone, free of charge. There is no registration, special links, or membership required to take advantage of its valuable resources. It’s the ultimate in democratization of knowledge access – a concept that is critical to us.

Ensuring our archive remains relevant requires an approach that makes learning about the past appealing to both current and future generations. One way we accomplish this is by making stories personal, so they relate to those visiting our archive and allow them to connect with the past. At a fundamental level, every story is a human story, and highlighting that is a compelling way to keep the archive relevant to researchers and the public.

Q: What advice would you give to organisations or families that are trying to preserve their legacies?

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to preserving a legacy. Every story is different, and the way individuals choose to archive it will also vary. The materials and formats used, whether documents, videos, or photographs, will reflect personal styles and perspectives. But what remains universal is the power of storytelling.

There are also practical considerations: how the archive will be maintained, how knowledge will be passed down, and how future generations will engage with it.

Building an archive is a long-term commitment. It’s not a sprint; it’s a marathon.

A piece of advice I was given early on when I spoke to archival experts was to never think something is too trivial to publish, For example, a tiny newspaper clipping might later anchor an entire story. Building an archive is like looking at life through a microscope: what initially appears insignificant can, with time and context, become profoundly meaningful.

Publication Date: 27-November-2025